Minimum Wage for One, Minimum Wage for All

By: Sara Fradi, 2L at the Seattle University School of Law, Law Clerk at HWS Law Group

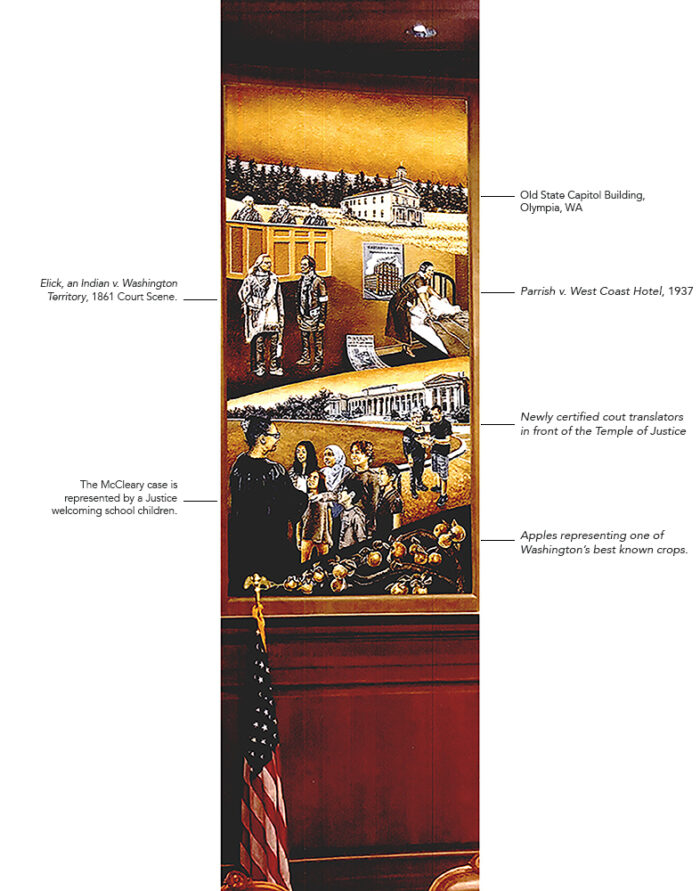

In light of the monograph being moved to the Chelan County Courthouse where the West Coast Hotel Co v. Parrish was originally tried, the WSCHS thought a review of the case was warranted (it is featured on this panel of the monograph).

The minimum wage provision has long been a contested matter in constitutional, labor and employment law. Due to the varying cost of living standards, among the fifty states, and varying cities in the United States, there is a federal minimum wage, a state minimum wage, and a local city minimum wage requirements. Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), the current federal minimum wage requirement for covered nonexempt employees is $7.25 per hour. The Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division is tasked with enforcing the federal minimum wage law. The Washington State Department of Labor and Industries, 2024 minimum wage requirement for Washington State is $16.28 per hour. However, the minimum wage requirement varies among the different cities in Washington, such as $19.97 per hour in Seattle, and $20.29 per hour in Tukwila. These minimum wage requirements are administered and enforced for all workers regardless of race, color, religion, sex, and national origin – per Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Equal Pay Act further requires that men and women be given equal pay for equal work if in the same workplace. The job does not need to be equal in position, but substantially equal. Despite this current layering of legislation for minimum wage requirements, it has not always been this way. In fact, prior to the renowned West Coast Hotel Co. V. Parrish case, there was no constitutional basis for equality in the enforcement of minimum wage requirements regarding sex. See West Coast Hotel Co. V. Parrish, 300 U.S. 379, 57 S.Ct. 578, 81 L.Ed. 703 (1937). In this article, this case’s implications in shaping the future for constitutional and employment and labor law will be discussed in detail.

West Coast Hotel Co. V. Parrish

Summary of Facts

The appellee, Elsie Parrish, was employed at the appellant’s hotel as a chambermaid from August 1993 to May 1995 before being discharged. Parrish v. West Coast Hotel Co., 185 Wash. 581, 582, 55 P.2d 1083 (1936). The appellee was paid at an agreed wage which was less than the fixed weekly minimum wage of $14.50, for a 48-hour-week, as established by the Industrial Welfare Commission under section 3, chapter 174, Laws 1913. Id. The Supreme Court of Washington had calculated that the appellant owed the appellee $17 if based on the payable wage, and $216.19 if based on the minimum wage requirement established by the Industrial Welfare Commission. Id. Following her discharge, the appellee with her husband sued the appellant demanding the difference between her wages and the minimum wage fixed by state law West Coast Hotel Co. V. Parrish, 300 U.S. 379, 388 (1937). The appellee fought her case arguing that her lack of payment was unacceptable under the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States of America. Id. The United States Supreme Court concluded that if the purpose of state regulation is to promote employee welfare, then it would be permissible.

Procedural History

The case had started off at the Chelan County Superior Court which ruled in favor of the appellant, as the court found that chapter 174, p. 602, Laws 1913 of the Industrial Welfare Commission, as applied to adult women was an “unconstitutional interference with the freedom of contract included within the guaranties of the due process clause of the Constitution of the United States.” Parrish v. West Coast Hotel Co., 185 Wash. 581, 582-583 (1936). The appellee then appealed, with her husband, to the Supreme Court of Washington, which relied on Larsen v. Rice to hold that instead of the case being a private concern, it is a public concern. Id. At 596. The court also found that the State’s interest to uphold enforcing minimum wage even of a private company for a female worker is constitutional. Id. At 597. The Supreme Court of Washington further mentions that as the United States Supreme Court had yet to hold that any statutes relating to the case has been deemed unconstitutional, and refused to adopt the holding in Adkins v. Children’s Hospital, instead adopting the Larsen v. Rice decision. Id. The Supreme Court of Washington reversed the trial court’s decision and had the cause remanded. Id. The Court also gave instructions for the trial court to enter judgement in favor of Parrish with an amount equal to the difference, between the amount paid, and the amount due under the minimum wage law. Id. The West Coast Hotel Company then appealed the decision at the United States Supreme Court.

The United States Supreme Court Opinion

The United States Supreme Court’s decision on the case was 5-4 and was delivered by Chief Justice Hughes. West Coast Hotel Co. V. Parrish, 300 U.S. 379, 386 (1937). The court analyzed the constitutional validity of the minimum wage law of Washington State in relation to the “Minimum Wages for Women Act.” Id; See Laws 1913 (Washington) c. 174, p. 602, Remington’s Rev.Stat.(1932) s 7623 et seq.

The Court’s Majority Opinion (As presented by Chief Justice Chales Evans Hughes):

The U.S Supreme Court -started its reasoning by making a fresh consideration of the Adkins v. Children’s Hospital case which the appellant relied on. West Coast Hotel Co. V. Parrish, 300 U.S. 379, 389 (1937). This was because Washington State had long upheld the minimum wage statute as a “reasonable exercise of the police power of the state.” Id. The court then presented a brief history of the litigation surrounding the minimum wage statute of Washington which was enacted in 1924. Id. Despite the court discussing the minimum wage statutes of other states being viewed as invalid in the past, the Washington State minimum wage statute stayed strong. Id. At 390-391. The Court then discussed the freedom of contract in relation to the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Id. At 391. The Court clarified that though liberty is mentioned in the Fourteenth Amendment, it must be distinguished in this case to reflect liberty “in a social organization which requires the protection of law against the evils which menace the health, safety, morals, and welfare of the people. Liberty under the Constitution is thus necessarily subject to the restraints of due process, and regulation which is reasonable in relation to its subject and is adopted in the interests of the community is due process.” Id. The Court made the conclusion that although adults are free to enter contracts, the importance of the freedom to contract is its applicability to public interest. Id. At 397-398. The Court further challenged the Adkins case by emphasizing that the “health of women and protection from unscrupulous and overreaching employers,” is of great public interest. Id. At 398. Emphasis was placed on the Legislature adopting the minimum wage statute for the purpose of protecting workers from exploitation at wages which did not cover the basic living necessities to prevent the evils of the “sweating system.” Id. At 398-399. The Court also mentioned the lack of bargaining power that workers have which placed them at a further disadvantage. Id. At 399-400. As such, legislative judgement was deemed necessary by the Court as a representation of the state’s exercise of its “protective power.” Id. At 400. The Court’s majority opinion concluded by overruling Adkins v. Children‘s Hospital and affirming the Supreme Court of Washington’s decision. Id.

The Court’s Dissenting Opinion (As Presented by Justice George Sutherland):

The dissenting opinion focused on the importance of the Constitution being seen as the highest binding power in law. Id. At 404-405. While the Fourteenth Amendment allowed for the freedom of contract, and was no longer open for question; contracts of employment was not included in the rule. Id. At 405. Give this, the dissenting opinion stated that as women and men stand equally legally and politically, there was no reason to distinguish the right to contract. Id. At 412. As such, a difference in sex was not a reasonable ground for making a restriction applicable to wage contracts; the dissenting justices believed that it created arbitrary discrimination. Id. At 413. The dissenting opinion reasoned that the ability to bargain did not depend on sex, and as in Adkins, if the Washington State minimum wage law state was unconstitutional for men, then it would also be unconstitutional for women. Id. The dissent concluded that the minimum wage law statute of Washington would not be unconstitutional in nature as it fixed wages in “the various industries at definite sums and forbidding employers and employees from contracting for any other than those designated.” Id. It also mentioned the risk of how setting a minimum wage standard might allow for a maximum wage standard to be introduced by employers. Id. The risk would then allow for the minimum and maximum wage standards to meet and become the same, to any wage, or employment contract to be abrogated. Id. At 413-414.

The Implications of the Ruling

Apart from the constitutional implications of this ruling, it also marked a change in the way the United States Supreme Court viewed a state’s power in regulating employer to employee relations. Thus providing, a major shift in labor and employment law as well as a shift from the Court’s prior decision on Lochner v. New York. A shift which marked the ending of the United States Supreme Court’s tendency to invalidate any legislation which strived to regulate private business.

Afterword:

Despite the case being ruled upon some time ago, the principles are applicable even in our current day. Since the 1930’s, contracts have seen an upward trend of becoming more long-term and fluid. With this trend particularly gaining traction with the rise of technology and Artificial Intelligence, a state’s legislature role in regulating businesses has also become increasingly important. This is also true with the rise of employment and labor law cases concerning at-will employment contracts. As contract law continues to evolve, so will the applicability of the ruling on West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish. As a result, several questions might be asked, where will the freedom to contract take us in the future? Will it take us in a direction which would force us to increase state legislation? Or would it instead take us in a direction that could possibly argue more constitutional issues? And if so, will there be an increase in contract-related discussions in civil rights litigation? Or will there be a future case that changes the way the Supreme Court views contracts forever? All these questions are valid, but only time will tell.