History of the Temple of Justice

by David Peterson & Celeste Stokes

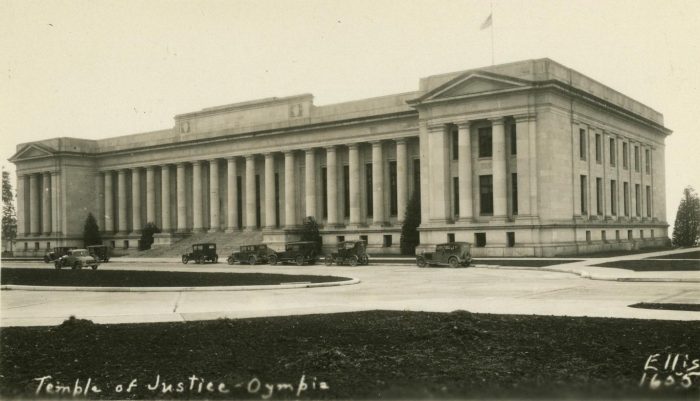

In 1911 Walter R. Wilder and Harry K. White, architects from New York, submitted the winning design for a group of buildings to comprise the state Capitol Campus, with the construction of the first building, the Temple of Justice. In the Spring of 1912, Chief Justice R. O. Dunbar presided over the official ground breaking ceremony.

Though still under construction, by December 1912 plans were approved to hold the 1913 Inaugural Ball of Ernest Lister, governor-elect, at the Temple. This was to be the largest and most elaborate inaugural ball to date. Excursions were run from Tacoma and Seattle to Olympia as large delegations were sent for the occasion, and Governor Hay placed the state naval training ship, Cheyenne, at the disposal of the Lister party to bring them from Tacoma. Temporary wooden floors were placed in the library, courtroom and foyer.

On January 15, 1913, Mayor Mottman and Mrs. Lister led 358 couples in the grand march of the Inaugural Ball. Total attendance was estimated between 1500 and 2000.

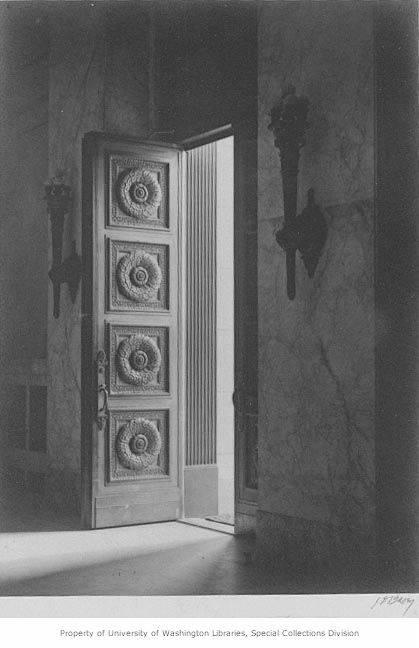

Between 1913 and 1920, the Supreme Court, Law Library and Attorney General’s Office conducted business while surrounded by laborers and tradesmen. During that time, the foyer was faced with white and gray Alaskan marble, furniture quality white oak was used throughout the building including in moldings, trim, doors & door frames, and original wood window frames were replaced with bronze. Outside, the brick exterior was faced with Wilkenson sandstone on a Baring granite base.

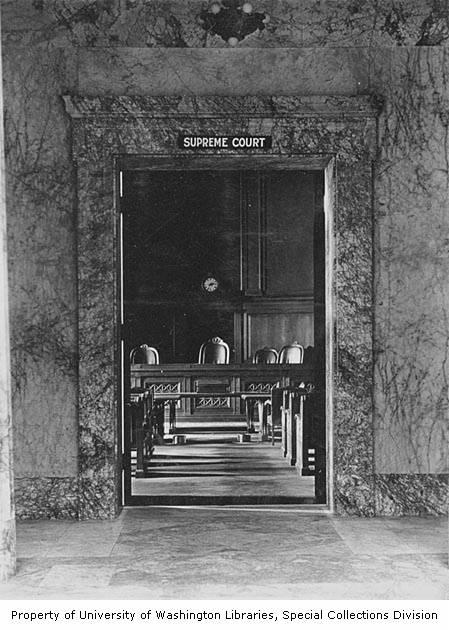

More than eight years following the initial groundbreaking, the Temple of Justice was accepted as complete. Oral arguments and other hearings were held in two court rooms, the main courtroom and a secondary “minor” courtroom (now the Chief Justice’s Reception Room.) Most cases were heard by a department of the court, each composed of the Chief Justice and four associate Justices. Since establishment of the Court of Appeals in 1969 all cases are heard en banc (by the full court.)

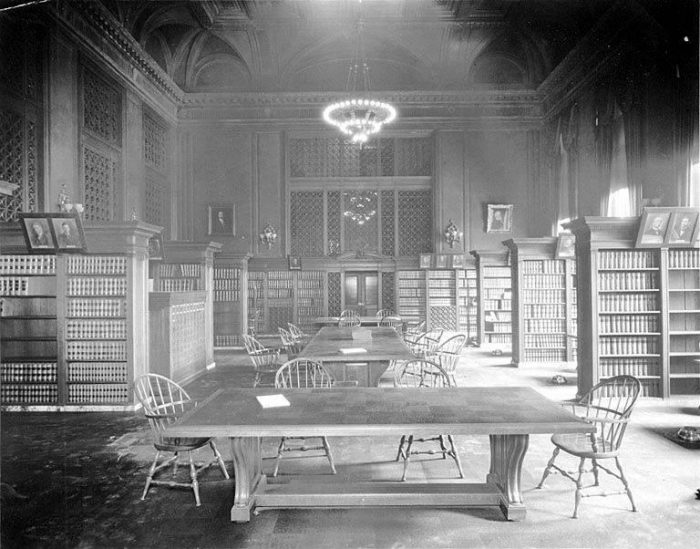

When the Temple opened in 1913, the Law Library (a division of the State Library at the time) was destined for the Main Reading Room. The remainder of the State Library collection was “temporarily” crammed into a few rooms on the lower floor of the Temple.

In 1958, the State Library moved to a new building (Prichard Building) while the Law Library remained in the Temple of Justice as originally planned. In 1959, the Law Library joined the judicial branch. Attorneys, law clerks and state employees would spend hours in the Law Library using indexes, law journals and researching cases.

A 1984 structural report came to the alarming conclusion that the Temple of Justice could not withstand another earthquake. Major structural problems included unreinforced concrete in the foundation and walls, and much of the brick masonry was cracked.

In 1987, the Supreme Court, Law Library and Attorney General’s Office moved out while the building underwent a two year seismic renovation. Progress was slow as workers built a new foundation under the building, ran steel bars from foundation to roof, a fire sprinkler system was added. Walls were enlarged or strengthened, resulting in a 10% loss of floor space in the foyer. At one point, work was halted after Carl Hilton, a construction worker, fell to his death.

In the end, the seismic renovation managed to make the Temple safer, while still preserving the building’s appearance and historical features. As Justice Andersen said at the building’s rededication ceremony “You’ve got to have the trappings of government. It has to look like a courthouse. It has to look like a Temple of Justice.”

Eleven years after the renovation completed, the 6.8 magnitude Nisqually Earthquake rocked the Temple of Justice on February 28, 2001. Plaster fell from the ceiling, chandeliers swung to and fro, and rows of books collapsed. Fortunately, no one was injured. While the building suffered extensive cosmetic damage, the 1980’s renovation kept structural damage to a minimum.

Once again, the foyer, courtroom and main reading room were closed as scaffolding was erected to first remove loose plaster from ceilings and then again the following summer to restore ceilings and walls. On the lower level, row after row of shelving was removed and replaced.

The electronic age brought change to how work is done in the Temple of Justice. Oral arguments and other hearings are now televised on TVW, allowing Washingtonians across the state to see the Supreme Court in action. Other changes are occurring behind the scenes, in management of case files and records retention.

Nowadays, some library customers ask their questions through email or chat rather than having to physically come to the library. On-site customers often use commercial databases to search a wide range of cases and law journals. Interlibrary loan allows libraries to share items, reducing the need for the library to have every legal book. This gives the library the opportunity to expand its reach far beyond the Olympia area.

Yet not everything is in electronic format, nor is it free of charge. Many library customers still find the information they seek is in books, and they need staff expertise to guide their research.

Through a century of change, the magnificence and grandeur of the Temple of Justice has continued to inspire those who walk through its doors. It will do so for another century.

Interior, Temple of Justice, detail of doors and Supreme Court chamber, ca. 1921. (Courtesy Univ. of Washington Libraries Special Collections)

David Peterson is a historic resource consultant and preservation planner based in Seattle and a board member of the Washington Courts Historical Society.

Celeste Stokes is a 40-year litigator with a love for Washington state history and obsession with courthouses. She is the president-elect of the Washington Courts Historical Society.