The Courts of the Washington Territory: 1853- 1889

by Gerry L. Alexander, Chief Justice of the Washington State Supreme Court (retired)

Prior to 1846, our nation's claim to the geographical area that later became the Washington Territory was very much in dispute.

Before 2003 fades into the past, Washingtonians should take a moment to note that it has been 150 years since the territory of Washington was created by act of Congress. To accord official recognition to this significant anniversary, a Territorial Sesquicentennial Commission was formed under co-chairs Secretary of State Sam Reed and First Lady Mona Lee Locke. I have had the honor to serve as the judiciary’s representative to that commission. My membership on the commission has led me to reflect on the 36-year period that Washington was a federal territory, and to focus on the court system that was extant then. 1 In doing so, I have concluded that a viable, vigorous, and independent court system existed in the territory. While it differed in some respects from the state system, we are familiar with today, it bore many of the same characteristics. I found also that the cases the territorial court system entertained, many of which are detailed in the three volumes of the Washington Territory Reports, constitute a great history of life and times in the territory.

A Territory Created

Prior to 1846, our nation’s claim to the geographical area that later became the Washington Territory was very much in dispute. The government of Great Britain, then the mightiest power in the world, was of the view that His Majesty’s claim extended as far south as the Columbia River. The government of the United States under President James K. Polk disagreed with that notion, contending that our nation’s claim extended up to roughly the 54th parallel and included much of present-day British Columbia. This led Polk’s presidential campaign to adopt the defiant slogan “Fifty-four-forty or Fight.” Happily, the dispute was largely settled in 1846 when the United States and Great Britain agreed to establish the international boundary at the 49th parallel from Point Roberts eastward to the crest of the Rocky Mountains.2 A line running along this parallel still marks the greatest portion of the western boundary between the United States and Canada.

In 1848, the Oregon Territory was organized to include land south of the 49th parallel, west of the Rockies, and north of California. This provided additional impetus to American settlers to move north of the Columbia River, and by 1852 there was significant interest among the occupants of this area to separate from Oregon. Consequently, a convention was held at Monticello (near present-day Longview) to prepare a petition to Congress asking that a federal territory north of the Columbia River be established. A memorial requesting creation of a new federal territory was thereafter sent to Congress by the Oregon Territorial Legislature. It noted that settlement was taking place in the Puget Sound country and stressed the hardships of travel and communication within an area as large as the Oregon Territory. In fact, the population of the area that was the subject of the memorial was not as great as the memorial implied, the settlers within the proposed territory numbering only about 4,000. Notably, the population of American Indians in the area was believed to be several times that number.

After considering the petition, Congress passed the Organic Act, which became effective on March 2, 1853, and established the government of the territory of Washington. Interestingly, Congress rejected suggestions that the new territory be named “Columbia,” believing that it would be confused with the District of Columbia. Apparently, no one was over-concerned that this territory might be confused with our nation’s capital, Washington, D.C. The territory created by the Organic Act included the area covered by present-day Washington, as well as what we now know as northern Idaho and western Montana. Upon Oregon’s 1859 admission to the Union as the 33rd state, the remainder of Idaho and a portion of present-day Wyoming were added to the Washington Territory. This large chunk of land did not remain in the territory for long, because in 1863 the Idaho Territory was created by Congress. This resulted in the Washington Territory being reduced to the size and shape of present-day Washington state.

Territorial Judges

Territorial status accorded the citizens of the new territory some advantages of self-government, but with limitations. The act creating the territory provided for an elected legislative assembly, consisting of a council and a House of Representatives, but indicated that any law passed by this assemblage had to be submitted to Congress and, if disapproved, was of no effect. Although the act provided that only white males aged 21 or older could vote at the first election or hold office, it also indicated that the legislative assembly could alter those requirements for future elections. The act also stated that the territory’s governor, secretary, and attorney, as well as its chief justice and two associate justices, were to be appointed by and serve at the pleasure of the President of the United States.

Other than what justice was meted out by local justices of the peace and probate judges, also provided for in the Organic Act, the judicial business of the territory resided with the appointed chief justice and associate justices. Each of them was responsible for conducting trials as a district judge in one of the territory’s three judicial districts, and all were required to reside in the district they served.

In December of each year, this trio of judges met in Olympia, and sat as justices of the supreme court of the territory. In this capacity, they heard any appeals from the decisions they had made as trial judges. This obvious conflict was obviated in 1884 when a fourth judicial district was added. This allowed the court to rotate membership so that a justice would not be called upon to review one of his own decisions. A total of 28 individuals served on the district/supreme court of the territory from 1853 until 1889, when Washington was admitted to the union. Despite the unattractiveness of serving in a large jurisdiction with inadequate means of travel, the territorial judges were generally of high caliber. The late Professor Charles H. Sheldon reflected on their collective qualities in his book A Century of Judging:

[A]s a group the judges were not all that different from their counterparts on the federal district court benches. The territorial judges, including Washington’s, were ambitious, successful, middle class lawyers who were among the educated elite. Their territorial service was often regarded as the culmination of a judicial career rather than merely a steppingstone toward higher political or judicial office.

Professor Sheldon also noted:

Among the several respected products of the territorial selection process who served on the Washington courts were Judges Edward Lander, John P. Hoyt, W. Lair Hill, Orange Jacobs, and Thomas Burke. Often the appointees were experienced in territorial affairs. Elwood Evans, who had been nominated but not confirmed, had served as secretary of the territory between 1862 and 1867; Orange Jacobs was a delegate to Congress (1875-79); Joseph R. Lewis had served on the Idaho and New Mexico Territorial Supreme Courts (1869-71 and 1871); Samuel C. Wingard had been U.S. Attorney; and John P. Hoyt had served as secretary and governor of the Arizona Territory (1876-79) and was nominated as governor of the Idaho Territory (1878).

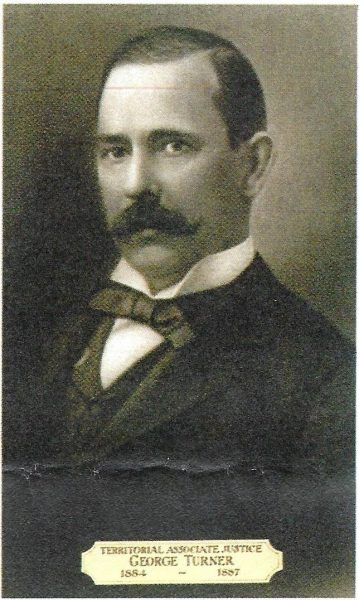

Despite the relatively high quality of the appointees, though, the citizens of the territory were never entirely satisfied with their judicial system, because little deference was given to local feelings on appointments, with more than one-half of the appointees hailing from outside the territory. This may have contributed to the strong support at the Constitutional Convention of 1889 for an elected judiciary. Significantly, the president of that convention was John Hoyt, who had served as a territorial judge from 1879 to 1887.3 An other former territorial judge, George Turner, served as chair of the Constitutional Convention’s important Judicial Department Committee.

Battle Between the Territorial Judges and the Governor

Although politics undoubtedly played an important part in the selection of the territorial judges, to their credit, they displayed a willingness to uphold the rule of law even when to do so put them at cross- purposes with the other two branches of the territorial government. Not surprisingly, the first interbranch clash occurred soon after the territory had come into existence. The court’s protagonist was none other than the formidable first governor of the Washington Territory, the dynamic and strong willed Isaac Stevens. The incident, which occurred in 1856, can only be described as bizarre.

The conflict began when several homesteaders, whom Governor Stevens deemed disloyal to his efforts to make war on Indians within the territory, were arrested by members of the volunteer militia of the territory and held in confinement in the Pierce County town of Steilacoom. In an effort to prevent the prisoners from being released by any judge, Stevens declared martial law in Pierce County. Territorial Chief Justice Edward Lander, acting at the behest of Associate Justice Francis A. Chenoweth, who was ill at the time, proceeded to Steilacoom to consider a petition for writ of habeas corpus that had been filed on behalf of the imprisoned settlers.4 A detachment of the volunteers interrupted Lander’s efforts to hold court and escorted the chief justice, his clerk, and his recorder to Olympia in Thurston County. Undeterred, Lander reconvened court in the capital city and issued the requested writ. The governor responded by expanding his martial law declaration to Thurston County.

Not one to be easily outflanked, Lander cited Governor Stevens for contempt and sent the court’s marshal to the governor’s office with a warrant for the governor’s arrest. Stevens had the marshal ejected and sent a company of volunteers to take Chief Justice Lander into custody and bring him to the governor. When the governor and judge came face to face, Stevens told Lander that he would set him free if he would agree not to hold court again until the governor told him he could. Lander courageously refused this offer and was locked up for his stand. A protest meeting in front of the governor’s office ensued, but was countered by an assembly of Stevens’s supporters.

All of this caused Justice Chenoweth to arise from his sickbed and travel to Steilacoom, where he proceeded to conduct court, but under the protection of a 50-man sheriff’s posse. The presence of the posse deterred the volunteers, who, acting on the sound advice of the commander of the U.S. Army garrison at Steilacoom, with drew. Stevens then terminated his declaration of martial law. Chenoweth followed with an order that all the governor’s prisoners, including the chief justice, be brought into court. Colonel Shaw of the volunteers refused to honor Chenoweth’s order, so the judge sent a U.S. marshal to arrest Shaw. The governor then capitulated and sent a letter to Chenoweth asking him to fine Shaw or release him, or both. Justice Chenoweth fined Shaw and sent him on his way but did not rescind the contempt warrant outstanding against the governor. Chief Justice Lander subsequently found Governor Stevens guilty of contempt and fined him $50. Stevens did not pay the fine, but his friends paid it for him, thus ending this strange event, which, despite its almost comedic quality, has to be viewed as an early victory for judicial independence and individual rights.

As a postscript, the territorial legislature passed a resolution censuring the governor for his conduct. This condemnation paled, however, in comparison to the rebuke Stevens received in a letter from the U.S. secretary of state, William F. Marcy. After indicating that martial law could not be justified when it acts against the existing government, Marcy said, “Your conduct in that respect does not therefore meet with favorable regard of the president.” Although we do not know what reaction Justices Lander and Chenoweth had to these official condemnations of Governor Stevens, one can only surmise that they felt vindicated and, perhaps, satisfied at the governor’s suffering from his own emotional wounds.

Olympia or Vancouver as Territorial Capital

Approximately five years after the legal battle between Governor Stevens and the territorial judges was resolved, the supreme court of the territory was for the first time faced with what it called the “grave and important question “of whether it should strike down an act of the territorial legislature an act purporting to move the territorial capital from Olympia to Vancouver.

By way of background, it should be noted that Olympia has always been Washington’s capital. That does not mean, however, that there have not been efforts over the years to wrest the seat of government away from Olympia. One of the most serious attempts took place in 1860, when law makers from Vancouver, working with legislators from Jefferson County who wanted a penitentiary for Port Townsend, and others from Seattle who coveted a territorial university for that city, managed to get a bill through the legislative assembly making Vancouver the capital. Inexplicably, another statute was passed that same session that put the question of the location of the territorial capital to the voters at the next election. The latter bill did not, however, say what effect this election would have, and it made no reference to the act’s making Vancouver the capital. Significantly, after the legislative session ended, it was discovered that both statutes were minus an enacting clause and an indication of the date of passage.

The legal effect of these defects was squarely presented to the Territorial Supreme Court, then consisting of Chief Justice Hewitt and Associate Justices Wyche and Oliphant, all appointees of President Abraham Lincoln. The case, which was captioned TheSeatofGovemment,1 Wash Terr. n6, came to the court in its December term of 1861, only the 30th case heard by the supreme court of the territory.

The case reached the court in a somewhat unusual manner. It had not been before any of the justices in their capacity as district judges; instead, the question was presented directly to them in their capacity as the Territorial Supreme Court in a pleading entitled “a plea of abatement of a writ of error.” In essence, this was a challenge to the court’s jurisdiction to hear any of the cases that had been docketed for that term in Olympia, on grounds that Olympia was not then the seat of government due to the action of the legislature. After considering the matter and observing that the legislature was assembled in Olympia in “an unorganized quorum awaiting the action of the supreme court,” and that “the controversy had been passed in review before the court and occupied more than three entire days in the discussion,” the court rendered its decision. In a well-crafted two-judge majority opinion, the flaws in the statute that purported to move the capital to Vancouver were discussed, and it was determined that the statute should be struck down because of the absence of an enacting clause and date of passage. In an obvious effort not to appear arbitrary, the majority prefaced its conclusion by saying that “a conflict of opinion between the legislature and judicial branches is always to be regretted, “but that if an act is “wanting in the requisite elements,” the court “is bound to declare it void and of no binding effect.”

In reaching its decision, the majority relied to some extent on the fact that the act of the legislature, which put the question of the location of the seat of government to a vote of the citizenry, had to be read in pari materia, “hand in hand,” with the Vancouver act and that both could not survive. That being the case, the majority indicated that it favored a decision consonant with the will of the public. It took note of the fact that Olympia had easily won the vote over Vancouver by a majority of 1,239 to 639. In a final rhetorical flourish, the majority said, as courts are wont to do today when they strike down an act of the Legislature for a technical failing, “if we have erred in refusing to give binding force and effect to this act, consolation remains that it is in the power of Congress, the territorial legislature, or the Supreme Court of the United States to correct the error, and the disappointed are not without remedy.”

Territorial Minorities

Needless to say, not every decision the judges of the territory made was as significant as the two I have just discussed. Many of the cases involved the more mundane, albeit important, issues that American courts traditionally confront, such as commercial disputes, garden-variety criminal cases, and dissolutions of marriage (“divorce” as it was then known). Not infrequently, though, the judges of the territory were called upon to consider weightier issues, such as the legal status of the most significant racial minority within the territory, Native Americans, as well as the rights of women. This article would be incomplete if it did not touch at least briefly on the court’s record in these areas.

Although I am hesitant to pass judgment on decisions made by judges at a time in the distant past when customs and practices were far different than they are today, I feel constrained to observe that the record of the territorial courts with respect to rights of women is spotty, at best. To its credit, the court admitted women to the practice of law as early as 1884. Furthermore, in that same year, a majority of the Territorial Supreme Court, over the dissent of Justice Turner, determined that women could serve as grand jurors. Rosencrantz v. Territory, 2 Wash. Terr. 267 (1884). Unfortunately, however, the court reversed that decision by another two-to-one vote only three years later in the case of Harland v. Territory, 3 Wash. Terr. 131 (1887). Not surprisingly, the majority opinion in Harland was written by Justice Turner, the dissenter in Rosencrantz. A year later, in the case of Bloomer v. Todd, 3 Wash. Terr. 599 (1888), a unanimous court concluded that an act of the legislative assembly, purportedly conferring upon women the right to vote, was void because it conflicted with the Organic Act. Although, as has been noted above, the Organic Act provided that the qualification of voters at elections after the first election shall be as prescribed by the legislature, the court concluded that voters had to be “citizens of the United States” and that the word “citizen” could be read as “male citizen.” Interestingly, although Judge Turner was no longer on the court when the Bloomer case was heard, he served as co-counsel in that case for the prevailing party.

The record of the Territorial Supreme Court in protecting the rights of Indians within the territory was, in my view, much better. Although its decision upholding the death sentence of the Indian leader Leschi (Leschi v. Washington Territory, 1 Wash. Terr. 13 (1857)) is generally considered a low point, the court did hold in Cho v. Julies, 1 Wash. Terr. 325 (1887), that Indians were capable of entering into binding contracts. In another decision, United States v. Taylor, 3 Wash. Terr. 88 (1871), which foreshadowed the famous “Boldt decision” of the modern era, it determined that the treaty right of Indians to fish in usual and accustomed waters could not be lawfully obstructed by a non-Indian homesteader who erected a fence that prevented Indians from exercising that right.

The most impressive decision relating to the rights of Native Americans, how ever, is an early decision of the Territorial Supreme Court in Elick v.Washington Territory, 1 Wash. Terr. 137 (1861). This decision, which came down only four years after the Leschi decision, contained the unanimous view of the three justices on the court, the same appointees of Abraham Lincoln who had decided the Seat of Government case. The facts there were that Elick, an Indian, had been found guilty by a jury of murder and was sentenced to death. The court, in a decision written on its behalf by Justice James Wyche, reversed the non-English-speaking defendant’s conviction on grounds that he had not been afforded an interpreter. The court said:

In any other view of the matter, his personal attendance would be a meaning less ceremony and the prisoner tried in violation of the laws and Constitution of the land. The Constitution of the United States is coextensive with the vast empire that has grown up under it, and its provisions securing certain rights to the accused in criminal cases, are as living and potent on the shores of the Pacific as in the city of it, birth. In the matter of these rights i1 knows no race. It is the rich inheritance of all, and under its provisions in the Courts of the country, on a trial for life the savage of the forest is the peer of the President.

I have to say that when I first read this, passage from Elick I was thrilled. One must keep in mind that this opinion was written more than 30 years before the U.S Supreme Court’s infamous decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, in which Justice Jahr Marshall Harlan wrote, albeit in dissent, that “our constitution is colorblind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.” I wondered to myself, could Harlan have known of Justice Wyche’s memorable words, that the Constitution “knows no race,” when he penned his famous words? Although we may never know the answer to that question, we can take pride in the fact that a court from which our state‘s present–day courts have descended recognized the fundamental responsibility that is placed on courts at all levels-to protect the rights of those in society who are least able to protect themselves. In all fairness, one would have to say that as lawyers and judges we have not always lived up to those noble words. But I hope that for the most part we have and will continue do so in the future. When we do, we should tip our hats to our judicial forebears who had the courage long ago to act in a way that set a shining example for us all to follow.

After serving for 20 years as a trial and appellate court judge, Gerry L. Alexander was elected to the Washington State Supreme Court in 1994- He was re-elected to the Court in 2000. In that same year his colleagues elected him to a four-year term as chief justice. Chief Justice Alexander has always had an abiding interest in history. He is a cofounder and board member of the Washington Courts Historical Society, and in 2000 he was selected as Olympia Historian of the Year.

NOTES

1. Only five of the 19 western territories created after 1850 stayed in territorial status longer than Washington. The average existence for all 19 post-1850 states was 27 years. Robert E. Ficken, Washington Territory (WSU Press 2002).

2. Great Britain and the United States did not entirely settle the boundary dispute until much later. The British continued to lay claim to San Juan Island, a position that was vigorously resisted by our nation. The dispute was settled in 1872 when the international arbitrator, Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany, awarded San Juan Island to the United States. It then became part of the Washington Territory, and the British withdrew a detachment of Royal Marines from the island.

3. Upon Washington's admission to the union, Hoyt was elected to the Supreme Court of the state of Washington. Thus, he had the distinction of being the only person to serve on both the Washington Territorial Supreme Court and the Washington State Supreme Court.

4. Because Judge Lander was an officer in the territorial volunteers, he found it necessary to resign his commission in order to act in the matter.