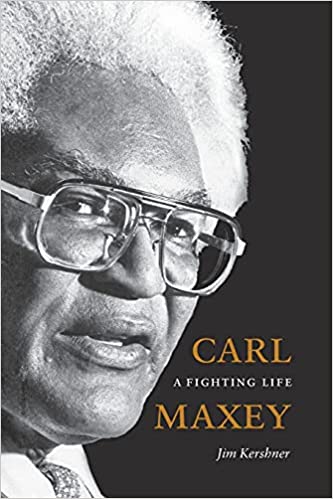

A moving tribute to the extraordinary life of a man who is best defined through a lifetime of service to the cause of equality, Jim Kershner’s book “A Fighting Life” details the humble beginning of twice-orphaned Carl Maxey. Carl Maxey’s life was deeply influenced by the abrupt end of his placement at the Spokane Children’s Home at the age of twelve. After spending his formative years as “a charge of the County,” Carl would learn that he and another young boy were evicted by the unanimous vote of the “good ladies of society” who decided to “have no more colored children in the Home.” Eventually, Carl would find a home in the most unlikely of places, at the Sacred Heart Mission on the Coeur d’ Alene Reservation. There, due to the kindness of Father Byrnes, a young orphan boy found hope and the necessary tools to succeed.

The book is set against the backdrop of social and political change during the Civil Rights Era in the mid-sized, northern city of Spokane, Washington. Without losing his way in nostalgia, Kershner celebrates Carl’s early success and fame as the first athlete to bring home a National Championship to Gonzaga University. Kershner details Carl’s life and career with punctuations of reality, reminding the reader that the same City that celebrated “King Carl’s” rousing victory also barred African Americans from the Davenport Hotel. And, though employed as a waiter at the Spokane Club, Carl had no chance of joining The Club as a member.

Kershner’s telling captures Carl’s unrelenting commitment to his sense of fairness and his life-long devotion to protect the rights of others. A devotion that would inform his work as an attorney on high-profile murder cases, the notorious “Seattle Seven Trial” and his work in local and national politics. But at the center of it all was a truth that Carl could always see. A truth that cost him and those he loved so much. A truth that often-rubbed others the wrong way.

Kershner includes local commentary and reported criticism from attorneys and judges who claim that Carl could, and would, turn any argument into one about “race” or “color.” Instead of pushing back, Kershner suggests this was employed by Carl to gain a legal advantage. But, for a child who lost his home due to the color of his skin, a young man who would serve the white elite their cocktails but could not shake their hand in membership, and as a man who would serve in the United States Army but could not sit next to a white soldier in the canteen. Perhaps it was this, not his exhaustion or his health, but Carl’s clear-eyed ability to see reality for what it was that brought an early end to his life. Perhaps he saw that beneath all the loss, the pain, the battles for equality on the Court steps and in Congress, it always was and had been about color.

A phenomenal read.